Charpentier Prelude From Te Deum Pdf File

[PDF + MP3 (digital sound)] - Viola (Alto), piano or organ - Baroque * License: Copyright © Dewagtere, Bernard - In the seventeenth century and eighteenth century, the composition of Te Deum-known in Europe a great vogue. This mode is clearly due to the political significance took this religious song. It was always sung.

The Te Deum (from its incipit, Te deum laudamus 'Thee, O God, we praise') is a LatinChristian hymn composed in the 4th century.It is one of the core hymns of the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Church with the Milanese Rite in the 6th to 8th centuries, and is sometimes known as 'the Ambrosian Hymn', even though authorship by Saint Ambrose is unlikely.

The term Te Deum can also refer to a short religious service, held to bless an event or give thanks, which is based upon the hymn.[1]

History[edit]

Authorship is traditionally ascribed to Saint Ambrose (d. 397) or Saint Augustine (d. 430).In 19th-century scholarship, Saints Hilary of Poitiers (d. 367) and Nicetas of Remesiana (d. 414) were proposed as possible authors. In the 20th century, the association with Nicetas has been deprecated, so that the hymn, while almost certainly dating to the 4th century, is considered as being of uncertain authorship. Authorship of Nicetas of Remesiana was suggested by the association of the name 'Nicetas' with the hymn in manuscripts from the 10th century onward, and was particularly defended in the 1890s by Germain Morin. Hymnologists of the 20th century, especially Ernst Kähler (1958) have shown the association with 'Nicetas' to be spurious.[2] It has been proposed based on the structural similarities with a eucharistic prayer that it was originally composed as part of one.[3]

The hymn was part of the Old Hymnal as it was introduced to the Benedictine order in the 6th century, and it was preserved in the Frankish Hymnal of the 8th century. It was, however, removed from the New Hymnal which became prevalent in the 10th century. It was restored in the 12th century in hymnals that attempted to restore the original intent of rule of St. Benedict.[clarification needed]

In the traditional office,[year needed] the Te Deum is sung at the end of Matins on all days when the Gloria is said at Mass; those days are all Sundays outside Advent, Septuagesima, Lent, and Passiontide; on all feasts (except the Triduum) and on all ferias during Eastertide.

Before the 1961 reforms of Pope John XXIII, neither the Gloria nor the Te Deum were said on the feast of the Holy Innocents, unless it fell on Sunday, as they were martyred before the death of Christ and therefore could not immediately attain the beatific vision.[4]

In the Liturgy of the Hours of Pope Paul VI, the Te Deum is sung at the end of the Office of Readings on all Sundays except those of Lent, on all solemnities, on the octaves of Easter and Christmas, and on all feasts.[5] A plenary indulgence is granted, under the usual conditions, to those who recite it in public on New Year's Eve.[6]

It is also used together with the standard canticles in Morning Prayer as prescribed in the AnglicanBook of Common Prayer,[year needed] in Matins for Lutherans,[year needed] and is retained by many churches of the Reformed tradition.[year needed]

The hymn is in regular use in the Catholic Church, Lutheran Church, Anglican Church and Methodist Church (mostly before the Homily) in the Office of Readings found in the Liturgy of the Hours, and in thanksgiving to God for a special blessing such as the election of a pope, the consecration of a bishop, the canonization of a saint, a religious profession, the publication of a treaty of peace, a royal coronation, etc. It is sung either after Mass or the Divine Office or as a separate religious ceremony.[7] The hymn also remains in use in the Anglican Communion and some Lutheran Churches in similar settings.

Text[edit]

The petitions at the end of the hymn (beginning Salvum fac populum tuum) are a selection of verses from the book of Psalms, appended subsequently to the original hymn.

The hymn follows the outline of the Apostles' Creed, mixing a poetic vision of the heavenly liturgy with its declaration of faith. Calling on the name of God immediately, the hymn proceeds to name all those who praise and venerate God, from the hierarchy of heavenly creatures to those Christian faithful already in heaven to the Church spread throughout the world.

The hymn then returns to its credal formula, naming Christ and recalling his birth, suffering and death, his resurrection and glorification. At this point the hymn turns to the subjects declaiming the praise, both the universal Church and the singer in particular, asking for mercy on past sins, protection from future sin, and the hoped-for reunification with the elect.

Music[edit]

| Problems playing these files? See media help. |

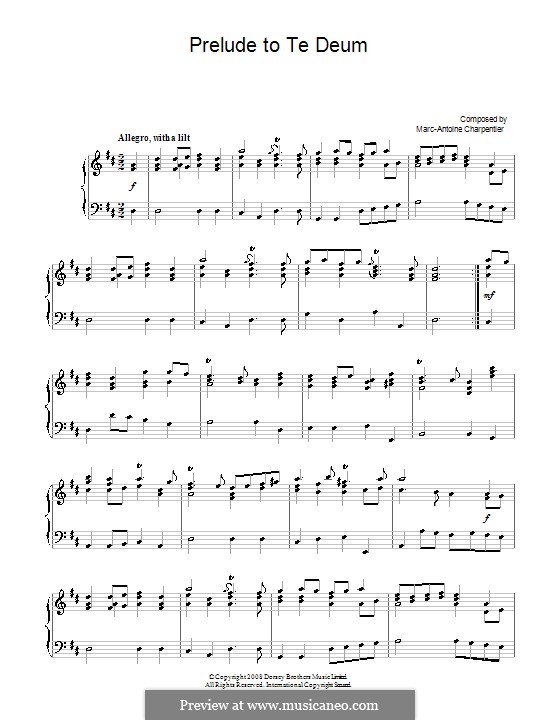

The text has been set to music by many composers, with settings by Haydn, Mozart, Berlioz, Verdi, Bruckner, Furtwängler, Dvořák, Britten, Kodály, and Pärt among the better known. Jean-Baptiste Lully wrote a setting of Te Deum for the court of Louis XIV of France, and received a fatal injury while conducting it. The prelude to Marc-Antoine Charpentier's setting (H.146) is well known in Europe on account of its being used as the theme music for some broadcasts of the European Broadcasting Union, most notably the Eurovision Song Contest. Earlier it had been used as the theme music for Bud Greenspan's documentary series, The Olympiad. Sir William Walton's Coronation Te Deum was written for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Other English settings include those by Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, Henry Purcell, Edward Elgar, and Herbert Howells, as well as three settings each by George Frideric Handel and Charles Villiers Stanford.

Puccini's opera Tosca features a dramatic performance of the initial part of the Te Deum at the end of Act I.

The traditional chant melody was the basis for elaborate Te Deum compositions by notable French organists Louis Marchand, Guillaume Lasceux, Charles Tournemire (1930), Jean Langlais (1934), and Jeanne Demessieux (1958), which are still widely performed today.

A version by Father Michael Keating is popular in some Charismatic circles. Mark Hayes wrote a setting of the text in 2005, with Latin phrases interpolated amid primarily English lyrics. In 1978, British hymnodist Christopher Idle[8] wrote God We Praise You,[9] a version of the text in 8.7.8.7.D meter, set to the tune Rustington. British composer John Rutter has composed two settings of this hymn, one entitled Te Deum and the other Winchester Te Deum. Igor Stravinsky set the first 12 lines of the text as part of The Flood in 1962. Antony Pitts was commissioned by the London Festival of Contemporary Church Music to write a setting for the 2011 10th Anniversary Festival.[10][11] The 18th-century German hymn Großer Gott, wir loben dich is a free translation of the Te Deum, which was translated into English in the 19th century as 'Holy God, we praise thy name.'[12]

Latin and English text[edit]

| Latin text | Translation from the Book of Common Prayer |

|---|---|

Te Deum laudámus: te Dominum confitémur. | We praise thee, O God : we acknowledge thee to be the Lord. |

In the Book of Common Prayer, verse is written in half-lines, at which reading pauses, indicated by colons in the text.

Service[edit]

A Te Deum service is a short religious service, based upon the singing of the hymn, held to give thanks.[1] In Sweden, for example, it may be held in the Royal Chapel in connection with the birth of a Prince or Princess, christenings, milestone birthdays, jubilees and other important event within the Royal Family of Sweden.[13] In Luxembourg, a service is held annually in the presence of the Grand-Ducal Family to celebrate the Grand Duke's Official Birthday, which is also the nation's national day, on either 23 or 24 June.[14]

Examples[edit]

- Te Deum by Hector Berlioz

- Te Deum Laudamus, the second part of Symphony No. 1 in D minor ('Gothic') (1919–1927) by Havergal Brian

- Two settings by Benjamin Britten: Te Deum in C (1934) and Festival Te Deum (1944)

- Te Deum by Anton Bruckner

- Short Festival Te Deum by Gustav Holst

- Te Deum H 145 H 145 a (1670), Te Deum H 146 (1690), Te Deum H 147 (1690), Te Deum H 148 (1698-99) by Marc-Antoine Charpentier

- Te Deum from Paris & Te Deum from Lyon by Henry Desmarest

- Te Deum by Michel-Richard de Lalande

- Te Deum for Great Chorus by Louis-Nicolas Clérambault

- Te Deum by Antonín Dvořák

- Utrecht Te Deum and Jubilate (1713), Dettingen Te Deum (1743) by George Frideric Handel

- Te Deum by Joseph Haydn

- Te Deum by Herbert Howells

- Te Deum by Johann Hummel

- Te Deum by Zoltán Kodály

- Te Deum by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1677)

- Te Deum by James MacMillan

- Te Deum by Piers Maxim

- Te Deum by Felix Mendelssohn

- Te Deum by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Te Deum by Arvo Pärt

- Te Deum by Krzysztof Penderecki

- Te Deum by Antoine Reicha

- Te Deum by John Milford Rutter

- Festival Te Deum and Te Deum Laudamus by Arthur Sullivan

- 'Te Deum', the final part of Quattro pezzi sacri by Giuseppe Verdi

- Te Deum in Giacomo Puccini's Opera Tosca

- Te Deum by Karl Jenkins

- Te Deum Laudamus by Manuel Arenzana

- 'Te Deum' from Morning Service in E-flat major by John M. Loretz, Jr.

References[edit]

- ^ abPinnock, William Henry (1858). 'Te Deum, a Separate Service'. The laws and usages of the Church and clergy. Cambridge: J. Hall and Son. p. 1301.

- ^Springer, C. P. E. (1976). 'Te Deum'. Theologische Realenzyklopädie. pp. 24-.

- ^Brown, Rosalind (19 July 2009). 'On singing 'Te Deum''. www.durhamcathedral.co.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). 'Holy Innocents'. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^'General Instruction of the Liturgy of the Hours'. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^'Te Deum'. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^'The Te Deum (cont.)'. Musical Musings: Prayers and Liturgical Texts – The Te Deum. CanticaNOVA Publications. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^'Christopher Idle'. Jubilate.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^'The Worshiping Church'. Hymnary.org. p. 42. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^'lfccm.com'. lfccm.com. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^February 2011 from Jerusalem to Jericho at the Wayback Machine (archived 2011-07-28)

- ^'Holy God, We Praise Thy Name'. Cyberhymnal.org. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^'Te Deum'. www.kungahuset.se. Swedish Royal Court. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^'National Day in Luxembourg'. www.visitluxembourg.com. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

Charpentier Prelude From Te Deum Pdf Files

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Te deum. |

- Texts on Wikisource:

- Te Deum (original Latin)

- Te Deum (English translation)

- Te Deum in Service, Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris on YouTube

| Eurovision Young Musicians | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Music contest |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of episodes | 18 contests |

| Production | |

| Running time | 90 minutes (2010–12, 2018) 120 minutes (2014–2016) |

| Production company(s) | European Broadcasting Union |

| Distributor | Eurovision |

| Release | |

| Original release | 11 May 1982; 37 years ago – present |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | Eurovision Song Contest (1956–) Eurovision Young Dancers (1985–) Junior Eurovision Song Contest (2003–) Eurovision Dance Contest (2007–2008) Eurovision Choir (2017–) |

| External links | |

| Official website | |

The Eurovision Young Musicians (French: L'Eurovision des Jeunes Musiciens), often shortened to EYM, or Young Musicians, is a biennial classical music competition for European musicians that are aged between 12 and 21. It is organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and broadcast on television throughout Europe, with some countries holding national selections to choose their representatives for the contest.

The first edition of the Eurovision Young Musicians took place in Manchester, United Kingdom on 11 May 1982 and 6 countries took part. The contest was won by Markus Pawlik from West Germany, who played the piano. Austria is the most successful country in the Young Musicians contest, having won five times 1988, 1998, 2002, 2004, and 2014 respectively and has hosted the contest a record six times. The most recent edition of this competition took place in Edinburgh, Scotland on 23 August 2018 and was won by Ivan Bessonov, who played the piano for Russia.

- 1History

- 5Winners

- 7Notes and references

History[edit]

The Eurovision Young Musicians, inspired by the success of the BBC Young Musician of the Year, is a biennial competition organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) for European musicians that are 18 years old or younger. Some participating countries held national heats in order to select their representatives for the contest. The first edition of the Eurovision Young Musicians took place in Manchester, United Kingdom on 11 May 1982 and 6 countries took part.[1] Germany's Markus Pawlik won the contest, with France and Switzerland placing second and third respectively.[2] It was also notable that Germany won the Eurovision Song Contest 1982 just a few weeks earlier.[3]

The BBC Young Musician of the Year is a televised national music competition. Broadcast originally on BBC Two biennially, and then on BBC Four years later, despite the name, and hosted by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).[1] The competition, a member of European Union of Music Competitions for Youth, is designed for British percussion, keyboard, string, brass and woodwind players, all of whom must be eighteen years of age or under on 1 January in the relevant year.[4]

The competition was established in 1978 by Humphrey Burton, Walter Todds and Roy Tipping, former members of the BBC Television Music Department.[1]Michael Hext, a trombonist, was the inaugural winner. In 1994, the usage of percussion instruments was first permitted, alongside the existing keyboard, string, brass and woodwind categories.[1] Since its introduction, the allowance of percussion instruments has increased interest in the competition among young people.[1] The competition has five stages, which consist of regional auditions, category auditions, category finals, semi-finals and the final.[5] As a result of the success of the competition, the Eurovision Young Musicians competition was initiated in 1982.[1]

Instruments and their first appearance[edit]

List contains only televised finals (preliminary rounds or semi finals are not included).

| Order | Instrument | First appearance | Country | First performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Piano | 1982 | United Kingdom | Anna Markland |

| 2 | Clarinet | 1982 | France | Paul Meyer |

| 3 | Violin | 1982 | Norway | Atle Sponberg |

| 4 | Viola | 1984 | France | Sabine Toutain |

| 5 | Cello | 1984 | Switzerland | Martina Schuchen |

| 6 | Horn | 1988 | United Kingdom | David Pyatt |

| 7 | Accordion | 1990 | Belgium | Christophe Delporte |

| 8 | Harmonica | 1992 | Spain | Antonio Serrano |

| 9 | Trombone | 1994 | Switzerland | David Bruchez |

| 10 | Organ | 1994 | Denmark | Frederik Magle |

| 11 | Percussion | 1998 | United Kingdom | Adrian Spillett |

| 12 | Contrabass | 2000 | Hungary | Ödön Rácz |

| 13 | Trumpet | 2000 | France | David Guerrier |

| 14 | Harp | 2000 | Netherlands | Gwyneth Wentink |

| 15 | Saxophone | 2004 | Germany | Koryun Asatryan |

| 16 | Oboe | 2006 | Switzerland | Simone Sommerhalder |

| 17 | Flute | 2006 | Austria | Daniela Koch |

| 18 | Cimbalom | 2012 | Belarus | Alexandra Denisenya |

| 19 | Bassoon | 2012 | Czech Republic | Michaela Špačková |

| 20 | Kanun | 2012 | Armenia | Narek Kazazyan |

| 21 | Guitar | 2014 | Malta | Kurt Aquilina |

| 22 | Recorder | 2014 | Netherlands | Lucie Horsch |

| 23 | Double bass | 2016 | Austria | Dominik Wagner |

| 24 | Tamburica | 2016 | Croatia | Marko Martinović |

Format[edit]

Each country is represented by one young talented musician that performs a piece of classical music of his or her choice accompanied by the local orchestra of the host broadcaster and a jury, composed of international experts, decides the top 3 participants. From 1986 to 2012 and again in 2018, a semi-final round took place a few days before the Contest, and the jury decided as well which countries qualified for the final.[6]

A preliminary round took place in 2014, with the jury scoring each musician and performance, however all participating countries automatically qualified for the final.[7] The semi final elimination stage of the contest was expected to return in 2016.[8][9] However the semi-finals were later removed due to the low number of participating countries that year.[10]

Participation[edit]

Eligible participants include primarily Active Members (as opposed to Associate Members) of the EBU. Active members are those who are located in states that fall within the European Broadcasting Area, or are member states of the Council of Europe.[11]

The European Broadcasting Area is defined by the International Telecommunication Union:[12]

- The 'European Broadcasting Area' is bounded on the west by the western boundary of Region 1, on the east by the meridian 40° East of Greenwich and on the south by the parallel 30° North so as to include the northern part of Saudi Arabia and that part of those countries bordering the Mediterranean within these limits. In addition, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and those parts of the territories of Iraq, Jordan, Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey and Ukraine lying outside the above limits are included in the European Broadcasting Area.[a]

The western boundary of Region 1 is defined by a line running from the North Pole along meridian 10° West of Greenwich to its intersection with parallel 72° North; thence by great circle arc to the intersection of meridian 50° West and parallel 40° North; thence by great circle arc to the intersection of meridian 20° West and parallel 10° South; thence along meridian 20° West to the South Pole.[14]

Active members include broadcasting organisations whose transmissions are made available to at least 98% of households in their own country which are equipped to receive such transmissions. If an EBU Active Member wishes to participate, they must fulfil conditions as laid down by the rules of the contest (of which a separate copy is drafted annually).[11]

Eligibility to participate is not determined by geographic inclusion within the continent of Europe, despite the 'Euro' in 'Eurovision' – nor does it have any relation to the European Union. Several countries geographically outside the boundaries of Europe have competed: Israel, Cyprus and Armenia, in Western Asia, since 1986, 1988 and 2012 respectively. In addition, several transcontinental countries with only part of their territory in Europe have competed: Russia, since 1994; and Georgia, since 2012. Listed below are all the countries that have taken part in the competition or are eligible to take part but have yet to do so.

Participation since 1982:Forty-two countries have participated in the Eurovision Young Musicians since it started in 1982. Of these, ten have won the contest. The contest, organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), is held biennially between members of the Union.

| Year | Country making its début entry |

|---|---|

| 1982 |

|

| 1984 | |

| 1986 |

|

| 1988 | |

| 1990 | |

| 1992 | |

| 1994 | |

| 1998 | |

| 2002 | |

| 2006 | |

| 2008 | |

| 2010 | |

| 2012 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2018 |

Hosting[edit]

Host cities of the Eurovision Young Musicians A single contest |

Most of the expense of the contest is covered by commercial sponsors and contributions from the other participating nations. The contest is considered to be a unique opportunity for promoting the host country as a tourist destination. The table below shows a list of cities and venues that have hosted the Eurovision Young Musicians, one or more times. Future venues are shown in italics. With 6 contests, Austria and its capital, Vienna have hosted the most contests.[16]

| Contests | Country | City | Venue | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Austria | Vienna | Musikverein | |

| Konzerthaus | ||||

| Rathausplatz | ||||

| 3 | Germany | Berlin | Konzerthaus | 2002 |

| Cologne | Cologne Cathedral | |||

| 2 | Switzerland | Geneva | Victoria Hall | 1984 |

| Lucerne | Culture and Congress Centre | 2004 | ||

| United Kingdom | Manchester | Free Trade Hall | 1982 | |

| Edinburgh | Usher Hall | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Denmark | Copenhagen | Radiohuset | 1986 |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | Concertgebouw | 1988 | |

| Belgium | Brussels | Cirque Royal | 1992 | |

| Poland | Warsaw | Philharmonic Concert Hall | 1994 | |

| Portugal | Lisbon | Cultural Centre of Belém | 1996 | |

| Norway | Bergen | Grieg Hall | 2000 | |

| Croatia | Zagreb | King Tomislav Square | 2020 |

Winners[edit]

As of 2018, there have been nineteen editions of the Eurovision Young Musicians competition, a biennial musicians contest organised by member countries of the European Broadcasting Union, with each contest having one winner.[17]

Winners by year[edit]

| Year | Date | Host City | Countries | Winner | Performer | Instrument | Piece | Runner-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 11 May | Manchester | 6 | Germany | Markus Pawlik | Piano | Piano Concerto No.1 by Felix Mendelssohn | France |

| 1984 | 22 May | Geneva | 7 | Netherlands | Isabelle van Keulen [nl] | Violin | Violin concert no. 5 op. 37 by Henri Vieuxtemps | Finland |

| 1986 | 27 May | Copenhagen | 15 | France | Sandrine Lazarides | Piano | Piano Concerto E flat by Franz Liszt | Switzerland |

| 1988 | 31 May | Amsterdam | 16 | Austria | Julian Rachlin | Violin | Concerto for violin and orchestra in d, op.22 by Henryk Wieniawski | Norway |

| 1990 | 29 May | Vienna | 18 | Netherlands | Niek van Oosterum [nl] | Piano | Concert for Piano and Orchestra a-minor op. 16, 1 Mov. by Edvard Grieg | Germany |

| 1992 | 9 June | Brussels | 13 | Poland | Bartłomiej Nizioł | Violin | Concerto for violin and orchestra in d major op. 77 by Johannes Brahms | Spain |

| 1994 | 14 June | Warsaw | 24 | United Kingdom | Natalie Clein | Cello | Cello Concerto in E minor, op. 85, part I by Edward Elgar | Latvia |

| 1996 | 12 June | Lisbon | 17 | Germany | Julia Fischer | Violin | – | Austria |

| 1998 | 4 June | Vienna | 13 | Austria | Lidia Baich [de] | Violin | Violin Concerto no. 5, 1st Mov. by Henri Vieuxtemps | Croatia |

| 2000 | 15 June | Bergen | 18 | Poland | Stanisław Drzewiecki | Piano | Piano Concerto in E minor, op. 11, 3rd movement by Frederic Chopin | Finland |

| 2002 | 19 June | Berlin | 20 | Austria | Dalibor Karvay | Violin | Carmen Fantasy by Franz Waxman | United Kingdom |

| 2004 | 27 May | Lucerne | 17 | Austria | Alexandra Soumm | Violin | Violin Concerto No.1 (1st Movement) by Niccolò Paganini | Germany |

| 2006 | 12 May | Vienna | 18 | Sweden | Andreas Brantelid | Cello | Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, 1st movement by Joseph Haydn | Norway |

| 2008 | 9 May | Vienna | 16 | Greece | Dionysis Grammenos [el] | Clarinet | Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra, 4th movement by Jean Françaix | Finland |

| 2010 | 14 May | Vienna | 15 | Slovenia | Eva Nina Kozmus | Flute | Concerto for flute, III. mov. Allegro scherzando by Jacques Ibert | Norway |

| 2012 | 11 May | Vienna | 14 | Norway | Eivind Holtsmark Ringstad [no] | Viola | Viola concerto, 2 & 3 mov. by Béla Bartók | Austria |

| 2014 | 31 May | Cologne | 14 | Austria | Ziyu He | Violin | 2. Violinkonzert by Béla Bartók | Slovenia |

| 2016 | 3 September | Cologne[18] | 11 | Poland | Łukasz Dyczko [pl] | Saxophone | Rhapsody pour Saxophone alto by André Waignein | Czech Republic |

| 2018 | 23 August | Edinburgh | 18 | Russia | Ivan Bessonov | Piano | 3rd mvt from Piano Concerto No. 1 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky | Slovenia |

| 2020 | 21 June | Zagreb[19] | 2 (to date) |

By country[edit]

The table below shows the top-three placings from each contest, along with the years that a country won the contest.

| Country | Total | Years won | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |

| Poland | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Germany | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Netherlands | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Norway | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |

| Slovenia | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| United Kingdom | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| France | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Russia | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | |

| Sweden | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Greece | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Finland | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | N/A |

| Switzerland | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | N/A |

| Croatia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| Czech Republic | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| Latvia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| Spain | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A |

| Armenia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Belgium | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Hungary | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N/A |

By instrument[edit]

As of 2018, twenty-four instruments have appeared at least once in the televised finals (preliminary rounds or semi finals are not included). The following seven have been played by a winner at least once.

| Instrument | Family | Total | Years won |

|---|---|---|---|

| Violin | Strings | 8 | |

| Piano | Keyboard | 5 |

|

| Cello | Strings | 2 | |

| Clarinet | Woodwind | 1 | 2008 |

| Flute | Woodwind | 1 | 2010 |

| Viola | Strings | 1 | 2012 |

| Saxophone | Woodwind | 1 | 2016 |

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The European Broadcasting Area was expanded in November 2007 by the World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC-07), also to include Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.[12][13]

- ^ abcdThe four Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden) originally sent a joint participant to the contest. In 1982, the musician represented the Norwegian colors and the Finnish colors in 1984.[15] The nations were represented individually, following the introduction of a preliminary round, at the 1986 contest.

References[edit]

- ^ abcdef'History. How it all started'. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ^'Eurovision Young Musicians 1982 (Participants)'. youngmusicians.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^'Eurovision Song Contest 1982'. eurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^'BBC Young Musician of the Year'. BBC. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^'Stages of the Competition'. BBC. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^'All you need to know about Young Musicians 2012'.

- ^'Steering Group meets in Cologne'. Youngmusicians.tv. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^'EYM'16: Return To 'Elimination Semifinal''. Eurovoix.com. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^Granger, Anthony (11 November 2015). 'EYM 16 semi final dates announced'. eurovoix.com. Eurovoix. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^'11 countries ready for Young Musicians 2016'. youngmusicians.tv. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ ab'Membership conditions'. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ ab'ITU-R Radio Regulations 2012-2015'(PDF). International Telecommunication Union, available from the Spectrum Management Authority of Jamaica. 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^'ITU-R Radio Regulations - Articles edition of 2004 (valid in 2004-2007)'(PDF). International Telecommunication Union. 2004.

- ^'Radio Regulations'. International Telecommunication Union. 8 September 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^'Eurovision Young Musicians 1986'. Issuu. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^'Eurovision Young Musicians - History by year'. youngmusicians.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^'Eurovision Young Musicians - History by country'. youngmusicians.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^'WDR and Cologne chosen to host 2016 competition'. Youngmusicians.tv. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^Zwart, Josianne (8 July 2019). 'Eurovision Young Musicians heading to Zagreb in 2020'. eurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

External links[edit]

- Eurovision Young Musicians – European Broadcasting Union